Review: Defective

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 2.6% of the adult population of the United States has bipolar disorder. While bipolar can be a challenging illness to diagnose and manage, it’s also possible to live a full, satisfying life once a person has found the right combination of treatments. Susan Sofayov’s novel, Defective, fictionalizes the process by which many people are diagnosed and cared for, and shows the impact mental illness can have on families, friends, and other loved ones.

The protagonist, Maggie Hovis, is a Pitt law school student who’s just been dumped by her fiance, Sam, because he can’t deal with her extreme mood swings. Being dumped sends Maggie into the tailspin that ultimately leads to her seeking help, being diagnosed with bipolar, and researching the (until-now secret) history of mental illness in her own family.

Because the story is told from Maggie’s point of view, she is not always the most reliable narrator, but that’s precisely the point: having bipolar can distort perception of self and others, so it’s almost necessary to take the journey from her pov, or else the impact of the story is lost. Sam, for example, is pretty much a jackass, and Maggie is definitely better off without him. However, from where she’s sitting, life has no meaning unless it’s got Sam. Being mired so deeply in Maggie’s perspective might be frustrating, but it’s an accurate representation of the thought processes to which many people are subject.

As Maggie learns to manage her illness, her focus shifts from Sam to her family history, a healthy inquiry that starts some good conversations within her family circle. Though not always pleasant, the things Maggie learns about her family history help her realize just how lucky she is to be living in a time where mental illnesses carry far less stigma than they used to. Arguably society has a long way to go in that regard, but Sofayov’s choice to emphasize the positive meshes nicely with the reappearance of Maggie’s old flame, Nick. Nick’s arrival, heavily foreshadowed in earlier chapters, will relieve readers who have grown weary of Maggie’s fixation on Sam. It’s at this point that the novel switches gears from problem novel to contemporary romance as Maggie sorts out her unresolved feelings about Nick.

There’s definitely a lot to chew on here, and the novel will be most interesting for readers who are willing to bumble through a whole lot of darkness before seeing the light. It will definitely be helpful to people who are themselves struggling with mental illness, or want to understand what’s going on with somebody they love. Therapists might want to check it out, too, to see if it might make good formal bibliotherapy or recreational reading for their clients.

Although we’ve made a lot of progress in the way we discuss mental health issues in contemporary culture, we’ll get even better if we read and listen to stories that feature patient-protagonists. Get your hands on a copy of Defective so you can see for yourself what Sofayov’s novel contributes to the conversation.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

Catch-up, Kindred

Some health issues have kept me from posting for a while. Luckily, while they are chronic, they are also very manageable. I’ve been focused on getting proper medical care, taking good care of myself, and letting my wonderful husband take care of me. Much to my relief, I’m feeling well enough to write again.

[You know it was pretty bad there for a while, because I only read eight books in September. Four fiction and four non-fiction, which brings my YTD total up to 117.]

October’s to-review pile is much larger, so I thought I’d start tackling it with a write-up of Octavia Butler’s classic speculative novel, Kindred.

Every time I read — or re-read — Butler’s work, I grimace at the utter unfairness that she isn’t here to keep astonishing us. What she left behind, however, in the time she had is, arguably, more than enough. Perhaps more than we, as a society, really deserve. Some people are way ahead of their time; Butler was definitely one of them.

Kindred is the story of Dana, a normal person hanging around her house, like you do, who is suddenly pulled backwards in time to the antebellum South. This would be cause for freakout for anyone, but Dana’s concerns are two-fold: not only is she at the mercy of some strange force, but that force has dumped her in the middle of a time period where she’s considered property instead of a person.

Not that she realizes this at first. On Dana’s first journey, all she sees is the little boy drowning, and so, of course, she saves him. Once the danger is past, it dawns on her that she’s not in California anymore…until, quite suddenly, she is again, much to her husband’s shock and consternation.

Dana’s time travel isn’t a one-off. Over the course of a few days she is repeatedly pulled backwards in time, and on each occasion she’s there to keep the same boy, Rufus, out of danger as he grows to manhood. Much to her horror, Dana slowly comes to realize that Rufus is one of her white ancestors, and that she is directly descended from the cruelty and abuses of slavery. So, stuck for long periods of time in an abusive past, with a jerk you have to keep safe because if you don’t, you’ll never be born.

Lovely.

Because time moves differently in Dana’s present, she can spend entire months on Rufus’s plantation and only be gone from her contemporary life for a few moments. The mechanics of time travel are not scientifically explained, but this isn’t hard sci-fi: this is a close look at what slavery was actually like, and it’s a rude awakening for Dana, who thought she understood what her ancestors had suffered. Her new-found knowledge cannot help but influence her contemporary life, and place a strain on her marriage (her husband is white).

Arguably, this is not a science-fiction novel. It’s really a horror novel with some time travel in it. Because what Dana — and, inevitably, the readers — experience is sheer horror at what human beings used to do to each other. History doesn’t get to stay safely dead and buried. She’s forced to live every excruciating detail. Worst of all? There’s no why, no grand reason or design behind it…and events that don’t seem to have any guiding intelligence behind them are the most horrific of all.

Most regular speculative fiction readers have read this novel before, but there’s so much going on here that multiple re-reads are more than justified. Even people who don’t normally care for SF/F will find a lot to chew on. It’s a disturbing novel, one to make you think and question. For, in the absence of a grand design, it’s up to the reader to make sense of Dana’s suffering, to ask what the point was…and then, what to do about it.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

Summer’s End Reading Tally

Well. That was a damn good time. More fun than I’ve had reading in ages.

When recommending books is a big part of how you earn your living, reading for pleasure can fall by the wayside. You read a lot of reviews, and you read 50 pages of everything you can get your hands on, in order to be able to sum it up and recommend it to someone else. And a book has to be pretty freaking brilliant for you to finish it.

But with the summer reading project, I got to be the person getting advice, which opened me up to a LOT of books I would have never picked up on my own. Not only will this make me a better reader’s advisor, it also gave me a little break from the status quo. Hearts! Unicorns! Rainbows!

Ahem. So, yes, a good time. Let’s crunch some numbers. These are my totals for the year, heading into fall/winter:

Fiction: 64

Non-fiction: 31

Poetry: 9

Drama: 2

Graphic Novels: 3

Grand total = 109 books.

That’s more than I read all last year, so I’m guessing my friends are great motivators, too. I have plans to finish all the books they suggested that I didn’t get to (next year I think I’ll cap the number of suggestions, as they clearly had more than I could reasonably read in a summer).

Coming up for fall: I’d like to finish the biggest challenge I’m working on, For Harriet’s 100 Books by Black Women Everyone Must Read. I’ve already started my next book, and hope to report back soon.

How was your summer reading? Any plans or high hopes for fall?

Filed under: Uncategorized | 4 Comments

From Manchester rain to West Coast sunshine we go, with Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore. A clever look at the interplay between print and digital technologies, wrapped up in a briskly -paced mystery (think Da Vinci Code light), Robin Sloan’s novel is a great pick for the Constant Reader who needs to lighten up a little, but not too much. Reading is, after all, serious business.

Clay Jannon, the protagonist, is not so much the hero of the book as he is the catalyst. A nice enough guy, but a bit of a bumbler, Jannon is the kind of person who innocently starts trouble and adventure by asking questions, poking his nose where it doesn’t belong, and otherwise being curious. That’s a great way to advance your plot, even if it does mean the reader ends up shaking her/his head a lot and saying, “Oh Clay. Really?” But yes, really. And because Jannon is a genuinely nice guy, it works.

After losing his job, Jannon stumbles across a “Help Wanted” sign at Mr Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore and figures, “Why not?” The store isn’t very busy at all, but there are regular customers, and soon enough Jannon notices a pattern to their behaviors. Using technology to unravel the pattern leads to Jannon’s initiation into a bizarre little literary group that’s been trying to unravel its founder’s secrets for centuries…but the head of the order is decidedly not a fan of using computers to make life easier, and warns Penumbra that his employee-disciple is cruising for a literary bruising if he doesn’t straighten up and fly right (by which he means, “old-school”).

Jannon, however, being a thoroughly modern type, sees only potential in Googling his way to arcane knowledge, and ropes his friends (plus a really cute techno-geek) into the greater mystery. Madcap hijinks ensue, and as readers learn more and more about the secret society and the information it’s trying to decipher, they will find themselves riveted to the series of puzzles, pranks, and adventures Sloan sets out for them. Punctuated by “Aha!” and “Wahoo!” moments at the high points, and “Aw, rats” events at the nadir, this is a fun little roller coaster of a book that will make both print aficionados and techno-geeks happy, especially since the merits and drawbacks of each kind of reading are addressed accurately in the course of the novel. In fact, you could say that the true message here (wrapped up like an Easter egg) is, “There’s plenty of room in the world for print texts and digital ones, so let’s stop arguing about it and just have a good time.”

The novel clocks in at 288 pages, but you’d never guess that from the sprightly pace that will keep you turning pages to find out what happens next. t’s the most delightful book about books and reading I’ve read in a long time, and the adventure tale it’s wrapped up in is so much fun, the book doesn’t feel the least bit didactic. Highly recommended to anyone looking for an up-beat summer read.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

Review: Vurt

Talk about a successful summer project. I’ve been so busy reading and enjoying the books my friends picked for me, the thought of reviewing them slipped right out of my mind. For the first time in a long time, I was reading for sheer enjoyment, instead of with an eye to analysis or criticism.

Not that those are bad things. But reading for pleasure alone, when you review and analyze books for a living, is the best feeling ever. It’s just you and the text. Like diving into the ocean, and letting surf carry you away for a while.

Inevitably, alas, you have to come back. It’s almost Labor Day, and soon my little project will be at an end. I’ll save all the numbers until then, but to get back into the swing of reviewing things, here’s a bit about one of my favorite summer reads, Jeff Noon’s Vurt.

Noon relentlessly plunges you into a world of made-up words and unfamiliar diction right from the very first page. If that sort of thing intrigues you, you’ll follow along and puzzle it out. Otherwise, you’ll put the book down in frustration and disgust. SF/F lovers, however, have always been an adventurous lot, so if you’re willing to work for it a bit–and you haven’t already read this classic novel–you’ll be well rewarded.

Still with me? All right then.

Our hero, Scribble, and his mates live in a Blade-Runner style world, only about 110% drearier because Manchester rain. To escape from their everyday lives, they take a lot of Vurt, a drug you imbibe by tickling the back of your throat with a feather. Each Vurt is a different color, indicating the kind of trip you’ll have…but taking Vurt is more than just a trip: it’s an inter-dimensional experience, and sometimes Very Bad Things can happen.

On one incredibly bad trip called English Voodoo, Scribble lost his sister, Desdemona, to the Vurt. Every trip he’s taken since then has been a valiant attempt to get her back, but with no leads or luck, Scribble’s at his wits’ end. The only thing he can think to do is find English Voodoo again and repeat his fateful trip in hopes of picking up some answers. But if you want to take something out of the Vurt, you need to be willing to leave something behind…

Reading Vurt is a what-is-this-I-don’t-even experience. Because it’s the first book in a trilogy, there’s a lot of set-up (specifically the chapters narrated by Game Cat, which only begin to make sense by the end of book 1 – keep going). Scribble’s friends and enemies are more types than well-rounded people, but the sheer variety of types (shadow-people, dog-men, bloblike jellies from other dimensions, etc.) is delightful. On top of that, Scribble’s love for his sister is so sincere that even after a few potentially squick-filled revelations, you still root for the guy.

Which brings us, I suppose, to a salient point: this is not a book for the easily offended, so if you’re one of those, you might want to wait for my next review. If, however, your punk sensibilities remain intact, and/or you’re just a broad-minded person to begin with, Vurt is a head-trip well worth taking. Or, as I’m fond of saying in other contexts, “It’s not nice…but it’s good.”

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

Review: Accelerando

It’s always a little awkward when you love an author, but not everything s/he wrote. This pops up a lot in SF/F, because writers are inclined to take more risks (which is excellent, and I encourage it). Still, people like what they like, and it’s really important to know which authors are consistent and which deliver change-ups, so you can tailor your recommendations based on what the potential reader will actually be into, and not just blanket recommend an author.

This brings us to one of my biggest nerd crushes, Charles Stross.

I love Charlie. I love the way his brain works. I love most of his ideas, and a lot of his novels (most notably, The Atrocity Archives, first in the Laundry Files series). However, despite the fact that it’s incredibly well-written, I did not enjoy Accelerando. So while I’m probably not the best reviewer for this book, I’m hoping I can set my personal heebie-jeebies aside long enough to describe Accelerando properly for those people who would really enjoy it.

Accelerando is, as the music buffs might have already guessed, the adventures of humanity after it finally takes the giant leap forward into Singularity. If you’re not familiar with the concept, take a few seconds to read the Wikipedia article (you must be this smart to participate in the SF/F community). If your gut response was, “Ugh,” this might not be the novel for you. If, however, you’re wondering where you can sign up for brain implants, you’ll most likely enjoy the misadventures of the Macx family as they bumble their way through a future where consciousness can live much longer than the body, several versions of yourself can be whizzing around at once, and death, as a concept, is pretty much obsolete, given that nanotechnology has figured out ways to give infinite reboots.

The plot revolves around Manfred Macx, a key player in accelerated technologies, who helps usher in the post-human era. His daughter, Amber, ups the ante by exploring outer space and dabbling in alien consciousness and technology. Amber’s son, Sirhan, is a digital archivist in a world decidedly not of his creation or choosing, trying to make sense of family ties while preserving the best of what used to be. Everyone is frightfully clever, everyone has accepted as many enhancements as they can stand (most of the characters spend most of the novel existing in virtual and/or digital form), and everyone is convinced there’s a technological solution for everything. The only problem is, nobody’s really very happy. Also (spoiler), cats are dicks (thanks to humans).

Not a comfortable read if, like me, you enjoy having a corporeal existence and are at peace with living out your natural lifespan and then dying. Then again, if I’m reading Stross correctly, these questions aren’t supposed to be comfortable, and they have to be asked. What is all of our technological progress for? We’re going admirably fast, it’s true, but where the hell are we going? Is Singularity everything it’s cracked up to be? Does the value of what we lose exceed the value of what we gain?

Good questions, written in a whip-smart tone, with a cheeky sense of humor. The paradox here is that readers most likely to love Stross have probably already read Accelerando, as well as his other work, and are, as we speak, composing intelligent responses to my clear failure to appreciate his genius. To which I can only say that questioning and challenging what you read is the highest compliment you can pay any author who is clearly questioning and challenging you.

O Accelerando! O humanity!

Now if you’ll pardon me, I’m going to go reread The Laundry Files in anticipation of The Rhesus Chart, which I will most decidedly be buying in meatspace, and not from asshats at Amazon (click if you don’t know what they’ve done now).

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

Don’t let the size of this book fool you. The story is only 120 pages long, but Gabriel Garcia Marquez gives you a lot to absorb.

It’s the morning after a huge wedding in a small town. What most of the recovering revelers don’t know is that the groom took the bride back to her parents’ house in the middle of the night, in disgrace, because apparently she wasn’t a virgin. In many small towns, this is Kind of a Big Deal Still, so once they’ve got the name of the man responsible, the bride’s brothers set out to kill him…and they’re not very quiet about making their intentions known.

Santiago Nasar, however, has no idea he’s a walking dead man. This is in large part due to everyone else’s failure to do or say anything. A few people do try to warn him, but they can’t find him, or just keep missing him, or something. A few other people think it might be a good idea to do something, but are distracted by other things. A few more people think it might be a good idea to do something, but then decide not to, for various reasons (the main one being that it’s probably not a good idea to interfere with A Matter of Honor). It’s like a Rube Goldberg Machine of doom, and the inevitably the story eventually contains one very dead Santiago Nasar. Honor having been avenged, the bride’s brothers go to jail for a while, but then get to go on with their lives. And the disgraced bride eventually reunites with her husband many years later, after time has mellowed them both.

What really struck me about this story is how much human beings haven’t changed. The book was published in 1983, so for some readers there might be a temptation to say, “Well, that’s how it was ‘back then.'” But are we really any better or more evolved, as people? How many honor killings still take place all over the world, over the notion that maybe a woman would like to have choice and autonomy over her own body? Even in the supposedly liberal Western cultures, where virginity is less of a big deal (though still a deal), women’s sexuality is rigidly policed by codes that deem her either a prude or a slut if she chooses to play by her own rules. What’s interesting here is that it’s the man who is killed, while the woman gets to live and have a normal life; you could even make the argument that perhaps we have taken major steps backward.

We could talk about that all day, because it’s fascinating, but what I find even MORE interesting is the entire town’s complicity in the murder, which reminded me very much of what happened to Kitty Genovese. Even the townsfolk who feel moved to do something are trapped by the larger current of the bystander effect, some of which is fueled by the notion that Nasar has it coming, and some of which is driven by the fact that people had other things to do, and felt the situation was “not their problem.” Even the town priest, arguably the person in the best position to take a moral or ethical stand, succumbs to inactivity and indecision:

“The truth is, I didn’t know what to do,” he told me. “My first thought was that it wasn’t any business of mine but something for the civil authorities, but then I made up my mind to say something in passing to Placida Linero [Nasar’s mother].” Yet when he’d crossed the square, he’d forgotten completely. “You have to understand,” he told me, “that the bishop was coming on that unfortunate day.” At the moment of the crime he felt such despair and was so disgusted with himself that the only thing he could think of was to ring the fire alarm. –pg. 70

Ugh. Horrible. But we the readers probably shouldn’t get too far up on our high horses. Garcia Marquez’s story is a cautionary tale for us, as we go about our daily business: what is my responsibility to my neighbor? What will I do if I see somebody in need of help? What do I do if I know something bad is going to happen? Is it my business to intervene?

I could–and most likely will–read this story again and again, and want to talk about it with people. If you care, even just a little, about the world and your place in it, you might want to try it on for size and see what you think.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

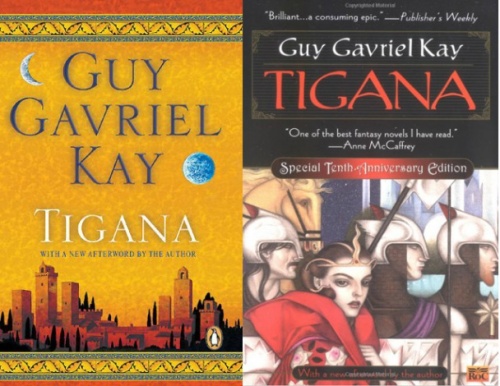

Review: Tigana

The best part about crowd-sourcing my summer reading list is that there’s a lot of sci-fi and fantasy on it. If I were only allowed to read one genre for the rest of my life, SF/F would be it. If some nitpick pointed out that that’s actually two genres (because, well, it is), I’d cheerfully pick F and spend the rest of my days surrounded by dragons, wizards, elves, orcs, thieves, vampires, witches, werewolves, and other such creatures battling the age-old war between good and evil in settings ranging from the idealized past to the urban future.

Guy Gavriel Kay’s Tigana is a solid example of why fantasy fiction brings me and many others so much joy. It’s the story of a land under a curse, the grief-stricken wizard who cursed it, and the men and women trying to break the curse. A book hasn’t made me gasp out loud in ages, but Tigana did it, and if you like medieval-style fantasy, you’re going to love this story.

Covers from different editions, courtesy of La Casa de El. Click through to read a review in Spanish.

Tigana is one country in a world where magic exists, but most of the inhabitants are human (supernatural creatures are frequently spoken of as legends, but very rarely seen). A generation ago, the Prince of Tigana murdered the wizard Brandin’s son in combat. Unfortunately, this only made Brandin more determined to conquer the country, and his forces pretty much reduced it to rubble. As if this weren’t enough of a lesson (NEVER underestimate the power of grief), Brandin curses the land so that nobody except people who were born there will be able to hear or speak the word “Tigana.” Everybody else will hear it as Charlie Brown adult wah-wah, which means that, in a generation, it will be as if the land and its history and culture had never existed.

The few remaining Tigana-born citizens who weren’t completely psychologically crushed by this state of affairs (most people fled to live incognito in other lands) still take it very, very personally, and have banded together to defeat Brandin and lift the curse. Posing as traveling musicians, they roam throughout the world sowing the seeds of rebellion while dodging Brandin and Alberico, another not-very-nice wizard who doesn’t give a damn about Brandin or Tigana: he just wants to be emperor someday, and to hell with everybody else. And then, in the time-honored trope of “stranger-dropped-in-the-middle-of-things,” a young singer named Devin falls in with the Tigana crew and learns that he isn’t really the person his parents always claimed he was.

And then things get…very interesting.

Like many fantasy novelists, Kay’s trying to do a lot here. What he manages to accomplish, within the framework of the traditional fantasy novel, is next to incredible, especially since the narrative pov frequently switches up between chapters (a technique that allows Kay to conceal some crucial information and set up those jaw-dropping plot twists). Tigana and the other lands of the Palm are closely modeled on Italy, and if you’ve read some Raven Grimassi in your day, certain plot elements will hit you with a shock of pleased recognition. There’s also Machiavellian politics going on mad like woah, and an official state religious structure as well as folk religious beliefs that inform the characters’ actions. Sex and relationships are somewhat fluid, though certain practices are still considered taboo (homosexuality and BDSM have their parts to play here, so if you’re easily offended, this might not be the book you’re looking for). Magic rests in the hands of only a few, and leaves behind traces of its use so that practitioners can be spotted (a dangerous prospect in a land ruled by cranky wizards who don’t want more competition). In the hands of a lesser novelist, all of these elements might make for a hot mess; Kay, however, weaves them all into a solid, action-packed narrative that will keep you turning pages long past your bedtime to see how it all fits together.

Basically, it’s the perfect book, and I plan on buying it for my home library. If you’re into SF/F, you’ve probably already read it, but hopefully I’ve inspired you to go back and read it again. My only regret about reading it is that now I can never again read it for the first time…but at least I can talk it up to other people. Five stars and much respect.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

Review: Mannequin Girl

By virtue of the fact that there’s something to read in every room in my house, I do manage to squeak in a few extra books each month (those 5-minute intervals add up). My most recent “bonus book” is Ellen Litman’s Mannequin Girl, an 80s coming-of-age story set in the Soviet Union.

We meet the protagonist, Kat Knopman, the summer before she enters first grade. Kat’s parents, who are both teachers, are brilliant, attractive, and well-liked, and Kat can’t wait to grow up to be just like them. However, her pre-school physical reveals that she has rapidly progressing scoliosis, a diagnosis that lands her in a school-sanitarium for children with physical disabilities and, eventually, confinement in a full-body brace.

The bulk of the novel revolves around Kat’s coming to terms with her disability (something she manages fairly well) and her parents’ failure to do the same. Her father, well-meaning Misha, pretends that Kat’s disability isn’t important. Though he’s kind enough about it, he isn’t willing to talk to Kat at length about her (or his) thoughts and feelings on the matter. Of course, given mama Anechka’s more dramatic responses, you could argue that Misha’s got his hands full already. Determined to have a “normal” child, Anechka subjects herself to a string of pregnancies and subsequent losses that wreck her both physically and mentally. Meanwhile, Kat bumbles through school and its social challenges, trying to figure out what her strengths and gifts are, and how she can use them to convince her parents she really is worthy of their love and attention.

It’s a bleak novel, to be sure, set as it is in a crumbling Soviet landscape. Kat’s survival is not a triumph of the will or a feel-good story: it’s just how things work. You make do with what you have and play the cards you’re dealt, because nobody’s coming around with new cards. As a little girl, Kat desperately wants Misha and Anechka’s love and approval, but over time, and with age, she learns to figure out what she wants for herself, and then to go get it (friendships, sex/love, some kind of career path, etc.). Although her path is still unclear at the novel’s end, the reader gets the sense that, free of the need to please her parents, Kat will succeed in life on her own terms.

Mannequin Girl is primarily a novel about children struggling to individuate from their parents, a process that is complicated by the presence of disability, and by the setting in a time period and culture with which the reader might not be familiar. There are a lot of “isms” floating around this book, including anti-Semitism, communism, and ableism, that make for a complex narrative not easily absorbed on one read. It’s not a feel-good book, but it is a think-well book, one you’ll be thinking about long after you’ve finished the last chapter. Recommended for people who like literary fiction, as well as stories about children and teens that aren’t necessarily YA lit.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

WHAT IS THIS I DON’T EVEN.

Ahem. That is to say, this isn’t a book you read casually. Here’s your litmus test. Did you like Dune? Awesome. Do you want to read a book that sees your Dune and raises you Judith Butler? If your answer was “Challenge accepted,” Stars is going to be your cup of tea. If not, leave now and wait for the next review. There’s no shame in it. Life is too short to spend with a book you might not like.

Still here? You’re going to be so very, very happy to have your mind blown by this exquisite novel, which is, at its core, a love story. What makes it an extraordinary love story is the universe in which it is set, one whose cultures are richly detailed, incredibly complex, and populated with all manner of extraordinary beings, meticulously detailed in appearance and behavior.

Plotwise, we begin on a world where anyone can have the anxiety centers of the brain removed. The catch is that you become a slave, but with no anxiety centers, you don’t worry too much about it. A man named Korga agrees to the procedure–known as Radical Anxiety Termination–and becomes known henceforth as Rat (see what he did there?) Korga. All manner of unpleasant things happen to Korga that are very upsetting for the reader, perhaps all the more so because Korga doesn’t really understand what’s happening to him–and is no longer able to care too much about it.

Meanwhile, on another world, a diplomat called Marq Dyeth is going about his normal (which is to say, packed with cultural and political intrigue) life when he receives word from a friend that a planet has been destroyed, and that the only survivor is about as close to Dyeth’s perfect erotic match as anyone can get. Intrigued, Marq allows circumstances to be carefully nudged so that the survivor will organically show up at his doorstep. It turns out to be Rat Korga, who has been healed of his wounds, but still doesn’t quite understand anything going on around him….except that he’s just as attracted to Dyeth as Marq is to him.

That’s an oversimplification by several thousand orders of magnitude, due largely to the fact that the plot itself moves very slowly, while the descriptions of history, culture, literature, anatomy, sexual practices, gender identity, and social customs go on for pages and pages, in the most utterly delightful way. It’s as if Delany has written, not just a novel, but a guidebook to a universe. In some ways it’s a far more open-minded, tolerant one than our own; in other ways, however, it is, sadly, just as barbaric as ours. A commentary, perhaps, on who we are, and who we could be?

The novel ends on an uncertain note, and while Delany planned to write a sequel, so far we’ve seen nothing. This is both a shame and a solace, because while you can’t go on to find out “what” happened, you can go back over and over to find out how things happened, and in what context. This is the kind of book you stay up all night talking about in the diner with your like-minded friends, over coffee and fried foods (or maybe pie), trying to unpack its richness and complexity.

Make mine a double, and pass the zucchini sticks. Recommended for extremely literate sci-fi fans or extremely literate people who scoff that there’s nothing of redeeming value in sf/f…just to see the looks on their faces when they are proved utterly, irrevocably wrong.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment